Fast Bayesian estimation of SARIMAX models¶

Introduction¶

This notebook will show how to use fast Bayesian methods to estimate SARIMAX (Seasonal AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average with eXogenous regressors) models. These methods can also be parallelized across multiple cores.

Here, fast methods means a version of Hamiltonian Monte Carlo called the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) developed by Hoffmann and Gelman: see Hoffman, M. D., & Gelman, A. (2014). The No-U-Turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 15(1), 1593-1623.. As they say, “the cost of HMC per independent sample from a target distribution of dimension

This notebook will combine the Python libraries statsmodels, which does econometrics, and PyMC3, which is for Bayesian estimation, to perform fast Bayesian estimation of a simple SARIMAX model, in this case an ARMA(1, 1) model for US CPI.

Note that, for simple models like AR(p), base PyMC3 is a quicker way to fit a model; there’s an example here. The advantage of using statsmodels is that it gives access to methods that can solve a vast range of statespace models.

The model we’ll solve is given by

with 1 auto-regressive term and 1 moving average term. In statespace form it is written as:

The code will follow these steps: 1. Import external dependencies 2. Download and plot the data on US CPI 3. Simple maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) as an example 4. Definitions of helper functions to provide tensors to the library doing Bayesian estimation 5. Bayesian estimation via NUTS 6. Application to US CPI series

Finally, Appendix A shows how to re-use the helper functions from step (4) to estimate a different state space model, UnobservedComponents, using the same Bayesian methods.

1. Import external dependencies¶

[1]:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import pymc3 as pm

import statsmodels.api as sm

import theano

import theano.tensor as tt

from pandas.plotting import register_matplotlib_converters

from pandas_datareader.data import DataReader

plt.style.use("seaborn")

register_matplotlib_converters()

/tmp/ipykernel_4908/3117040453.py:12: MatplotlibDeprecationWarning: The seaborn styles shipped by Matplotlib are deprecated since 3.6, as they no longer correspond to the styles shipped by seaborn. However, they will remain available as 'seaborn-v0_8-<style>'. Alternatively, directly use the seaborn API instead.

plt.style.use("seaborn")

2. Download and plot the data on US CPI¶

We’ll get the data from FRED:

[2]:

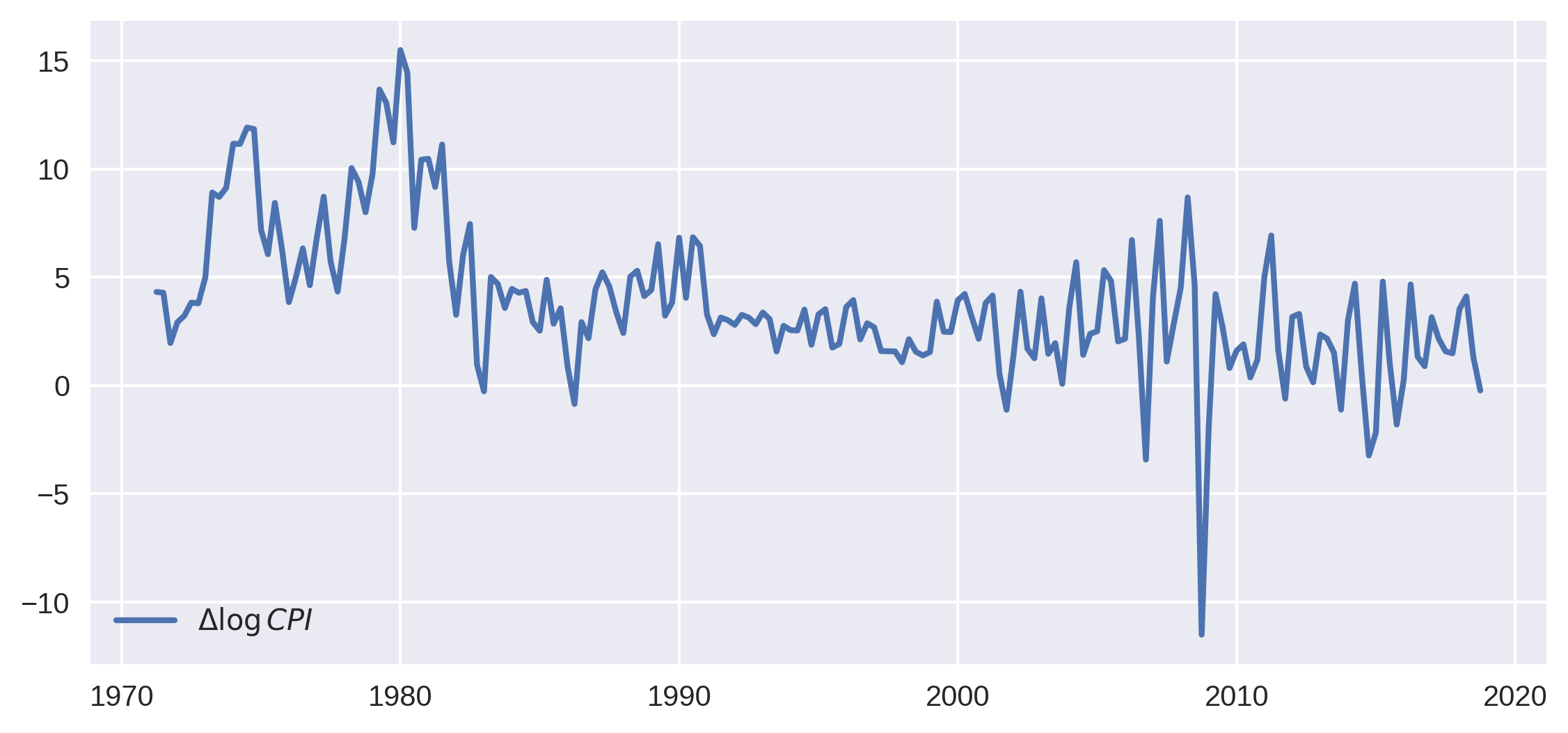

cpi = DataReader("CPIAUCNS", "fred", start="1971-01", end="2018-12")

cpi.index = pd.DatetimeIndex(cpi.index, freq="MS")

# Define the inflation series that we'll use in analysis

inf = np.log(cpi).resample("QS").mean().diff()[1:] * 400

inf = inf.dropna()

print(inf.head())

CPIAUCNS

DATE

1971-04-01 4.316424

1971-07-01 4.279518

1971-10-01 1.956799

1972-01-01 2.917767

1972-04-01 3.219096

[3]:

# Plot the series

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9, 4), dpi=300)

ax.plot(inf.index, inf, label=r"$\Delta \log CPI$", lw=2)

ax.legend(loc="lower left")

plt.show()

3. Fit the model with maximum likelihood¶

Statsmodels does all of the hard work of this for us - creating and fitting the model takes just two lines of code. The model order parameters correspond to auto-regressive, difference, and moving average orders respectively.

[4]:

# Create an SARIMAX model instance - here we use it to estimate

# the parameters via MLE using the `fit` method, but we can

# also re-use it below for the Bayesian estimation

mod = sm.tsa.statespace.SARIMAX(inf, order=(1, 0, 1))

res_mle = mod.fit(disp=False)

print(res_mle.summary())

SARIMAX Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: CPIAUCNS No. Observations: 191

Model: SARIMAX(1, 0, 1) Log Likelihood -448.685

Date: Wed, 02 Nov 2022 AIC 903.370

Time: 17:02:14 BIC 913.127

Sample: 04-01-1971 HQIC 907.322

- 10-01-2018

Covariance Type: opg

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ar.L1 0.9785 0.015 64.545 0.000 0.949 1.008

ma.L1 -0.6342 0.057 -11.073 0.000 -0.747 -0.522

sigma2 6.3682 0.323 19.695 0.000 5.734 7.002

===================================================================================

Ljung-Box (L1) (Q): 4.77 Jarque-Bera (JB): 699.70

Prob(Q): 0.03 Prob(JB): 0.00

Heteroskedasticity (H): 1.72 Skew: -1.48

Prob(H) (two-sided): 0.03 Kurtosis: 11.90

===================================================================================

Warnings:

[1] Covariance matrix calculated using the outer product of gradients (complex-step).

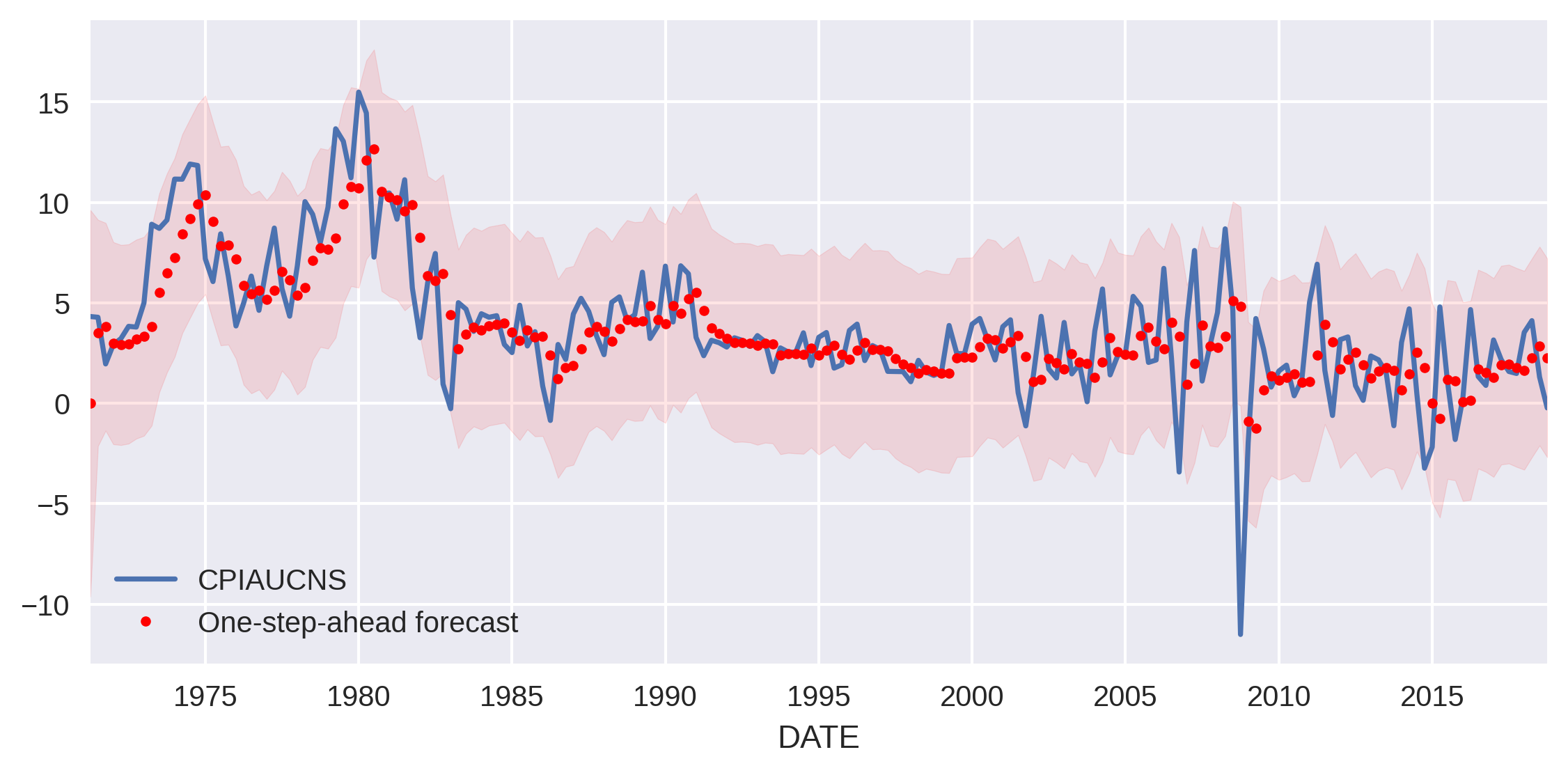

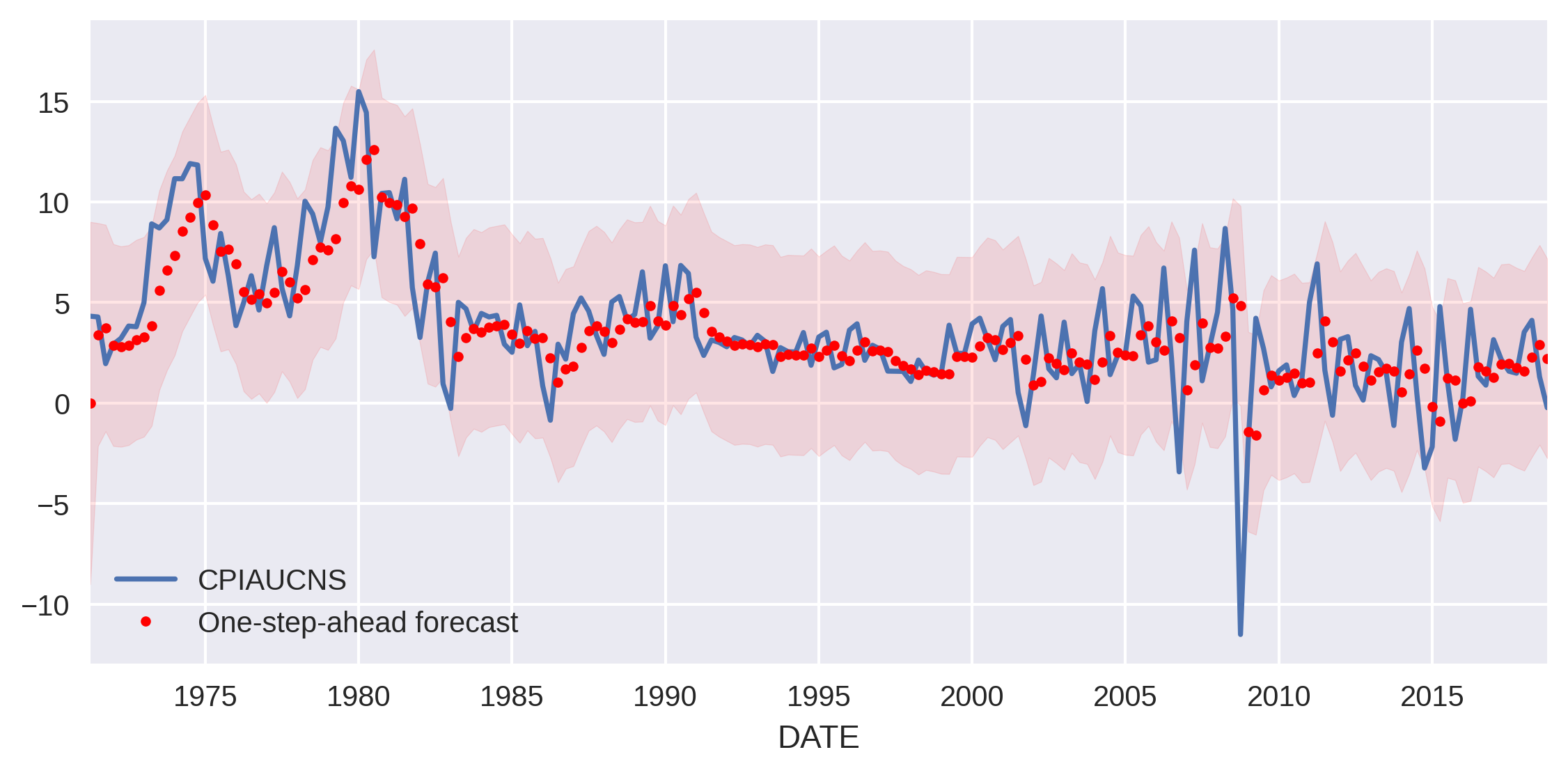

It’s a good fit. We can also get the series of one-step ahead predictions and plot it next to the actual data, along with a confidence band.

[5]:

predict_mle = res_mle.get_prediction()

predict_mle_ci = predict_mle.conf_int()

lower = predict_mle_ci["lower CPIAUCNS"]

upper = predict_mle_ci["upper CPIAUCNS"]

# Graph

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9, 4), dpi=300)

# Plot data points

inf.plot(ax=ax, style="-", label="Observed")

# Plot predictions

predict_mle.predicted_mean.plot(ax=ax, style="r.", label="One-step-ahead forecast")

ax.fill_between(predict_mle_ci.index, lower, upper, color="r", alpha=0.1)

ax.legend(loc="lower left")

plt.show()

4. Helper functions to provide tensors to the library doing Bayesian estimation¶

We’re almost on to the magic but there are a few preliminaries. Feel free to skip this section if you’re not interested in the technical details.

Technical Details¶

PyMC3 is a Bayesian estimation library (“Probabilistic Programming in Python: Bayesian Modeling and Probabilistic Machine Learning with Theano”) that is a) fast and b) optimized for Bayesian machine learning, for instance Bayesian neural networks. To do all of this, it is built on top of a Theano, a library that aims to evaluate tensors very efficiently and provide symbolic differentiation (necessary for any kind of deep learning). It is the symbolic differentiation that means PyMC3 can use NUTS on any problem formulated within PyMC3.

We are not formulating a problem directly in PyMC3; we’re using statsmodels to specify the statespace model and solve it with the Kalman filter. So we need to put the plumbing of statsmodels and PyMC3 together, which means wrapping the statsmodels SARIMAX model object in a Theano-flavored wrapper before passing information to PyMC3 for estimation.

Because of this, we can’t use the Theano auto-differentiation directly. Happily, statsmodels SARIMAX objects have a method to return the Jacobian evaluated at the parameter values. We’ll be making use of this to provide gradients so that we can use NUTS.

Defining helper functions to translate models into a PyMC3 friendly form¶

First, we’ll create the Theano wrappers. They will be in the form of ‘Ops’, operation objects, that ‘perform’ particular tasks. They are initialized with a statsmodels model instance.

Although this code may look somewhat opaque, it is generic for any state space model in statsmodels.

[6]:

class Loglike(tt.Op):

itypes = [tt.dvector] # expects a vector of parameter values when called

otypes = [tt.dscalar] # outputs a single scalar value (the log likelihood)

def __init__(self, model):

self.model = model

self.score = Score(self.model)

def perform(self, node, inputs, outputs):

(theta,) = inputs # contains the vector of parameters

llf = self.model.loglike(theta)

outputs[0][0] = np.array(llf) # output the log-likelihood

def grad(self, inputs, g):

# the method that calculates the gradients - it actually returns the

# vector-Jacobian product - g[0] is a vector of parameter values

(theta,) = inputs # our parameters

out = [g[0] * self.score(theta)]

return out

class Score(tt.Op):

itypes = [tt.dvector]

otypes = [tt.dvector]

def __init__(self, model):

self.model = model

def perform(self, node, inputs, outputs):

(theta,) = inputs

outputs[0][0] = self.model.score(theta)

5. Bayesian estimation with NUTS¶

The next step is to set the parameters for the Bayesian estimation, specify our priors, and run it.

[7]:

# Set sampling params

ndraws = 3000 # number of draws from the distribution

nburn = 600 # number of "burn-in points" (which will be discarded)

Now for the fun part! There are three parameters to estimate:

[8]:

# Construct an instance of the Theano wrapper defined above, which

# will allow PyMC3 to compute the likelihood and Jacobian in a way

# that it can make use of. Here we are using the same model instance

# created earlier for MLE analysis (we could also create a new model

# instance if we preferred)

loglike = Loglike(mod)

with pm.Model() as m:

# Priors

arL1 = pm.Uniform("ar.L1", -0.99, 0.99)

maL1 = pm.Uniform("ma.L1", -0.99, 0.99)

sigma2 = pm.InverseGamma("sigma2", 2, 4)

# convert variables to tensor vectors

theta = tt.as_tensor_variable([arL1, maL1, sigma2])

# use a DensityDist (use a lamdba function to "call" the Op)

pm.DensityDist("likelihood", loglike, observed=theta)

# Draw samples

trace = pm.sample(

ndraws,

tune=nburn,

return_inferencedata=True,

cores=1,

compute_convergence_checks=False,

)

Auto-assigning NUTS sampler...

Initializing NUTS using jitter+adapt_diag...

Sequential sampling (2 chains in 1 job)

NUTS: [sigma2, ma.L1, ar.L1]

Sampling 2 chains for 600 tune and 3_000 draw iterations (1_200 + 6_000 draws total) took 161 seconds.

There were 8 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 14 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

Note that the NUTS sampler is auto-assigned because we provided gradients. PyMC3 will use Metropolis or Slicing samplers if it does not find that gradients are available. There are an impressive number of draws per second for a “block box” style computation! However, note that if the model can be represented directly by PyMC3 (like the AR(p) models mentioned above), then computation can be substantially faster.

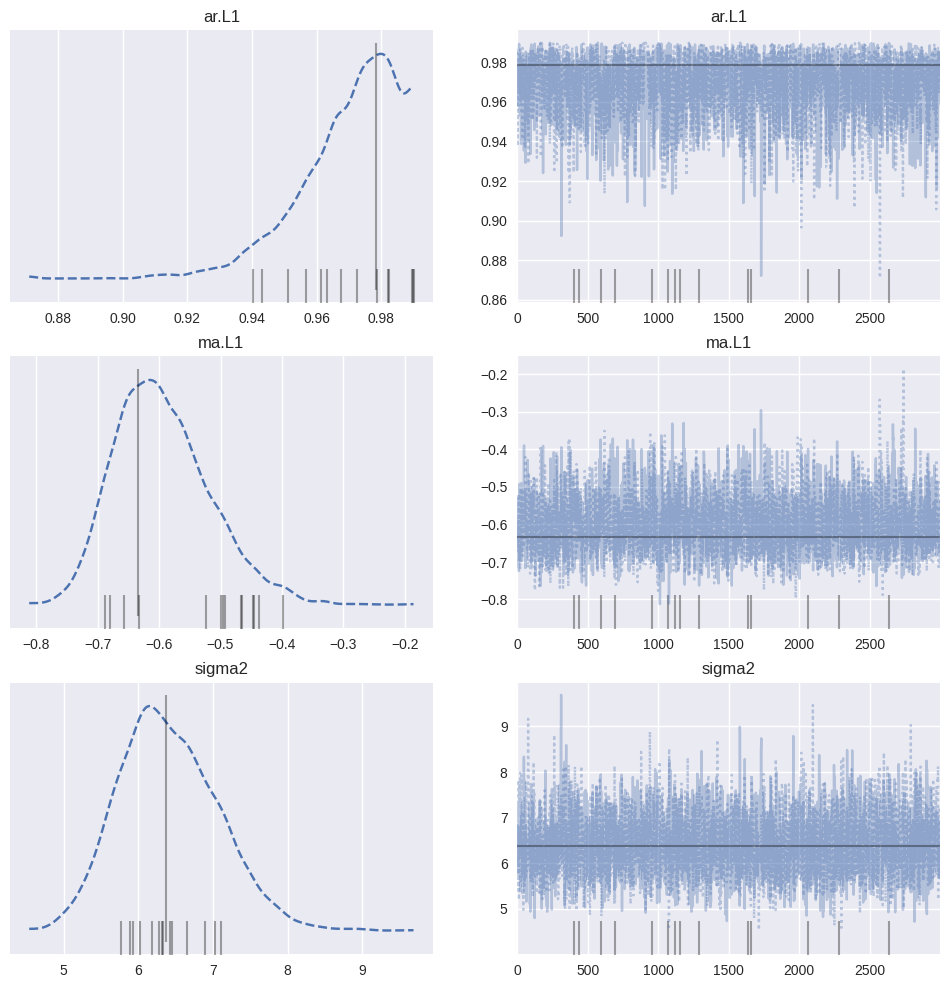

Inference is complete, but are the results any good? There are a number of ways to check. The first is to look at the posterior distributions (with lines showing the MLE values):

[9]:

plt.tight_layout()

# Note: the syntax here for the lines argument is required for

# PyMC3 versions >= 3.7

# For version <= 3.6 you can use lines=dict(res_mle.params) instead

_ = pm.plot_trace(

trace,

lines=[(k, {}, [v]) for k, v in dict(res_mle.params).items()],

combined=True,

figsize=(12, 12),

)

<Figure size 800x550 with 0 Axes>

The estimated posteriors clearly peak close to the parameters found by MLE. We can also see a summary of the estimated values:

[10]:

pm.summary(trace)

[10]:

| mean | sd | hdi_3% | hdi_97% | mcse_mean | mcse_sd | ess_bulk | ess_tail | r_hat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ar.L1 | 0.969 | 0.015 | 0.943 | 0.990 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1427.0 | 966.0 | 1.0 |

| ma.L1 | -0.595 | 0.077 | -0.729 | -0.447 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 1911.0 | 1803.0 | 1.0 |

| sigma2 | 6.411 | 0.662 | 5.199 | 7.609 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 2930.0 | 3041.0 | 1.0 |

Here

Additionally, the highest posterior density interval (the gap between the two values of HPD in the table) is small for each of the variables.

6. Application of Bayesian estimates of parameters¶

We’ll now re-instigate a version of the model but using the parameters from the Bayesian estimation, and again plot the one-step-ahead forecasts.

[11]:

# Retrieve the posterior means

params = pm.summary(trace)["mean"].values

# Construct results using these posterior means as parameter values

res_bayes = mod.smooth(params)

predict_bayes = res_bayes.get_prediction()

predict_bayes_ci = predict_bayes.conf_int()

lower = predict_bayes_ci["lower CPIAUCNS"]

upper = predict_bayes_ci["upper CPIAUCNS"]

# Graph

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9, 4), dpi=300)

# Plot data points

inf.plot(ax=ax, style="-", label="Observed")

# Plot predictions

predict_bayes.predicted_mean.plot(ax=ax, style="r.", label="One-step-ahead forecast")

ax.fill_between(predict_bayes_ci.index, lower, upper, color="r", alpha=0.1)

ax.legend(loc="lower left")

plt.show()

Appendix A. Application to UnobservedComponents models¶

We can reuse the Loglike and Score wrappers defined above to consider a different state space model. For example, we might want to model inflation as the combination of a random walk trend and autoregressive error term:

This model can be constructed in Statsmodels with the UnobservedComponents class using the rwalk and autoregressive specifications. As before, we can fit the model using maximum likelihood via the fit method.

[12]:

# Construct the model instance

mod_uc = sm.tsa.UnobservedComponents(inf, "rwalk", autoregressive=1)

# Fit the model via maximum likelihood

res_uc_mle = mod_uc.fit()

print(res_uc_mle.summary())

RUNNING THE L-BFGS-B CODE

* * *

Machine precision = 2.220D-16

N = 3 M = 10

At X0 0 variables are exactly at the bounds

At iterate 0 f= 2.43820D+00 |proj g|= 1.07332D-01

At iterate 5 f= 2.31427D+00 |proj g|= 2.20639D-02

At iterate 10 f= 2.30814D+00 |proj g|= 1.67045D-05

* * *

Tit = total number of iterations

Tnf = total number of function evaluations

Tnint = total number of segments explored during Cauchy searches

Skip = number of BFGS updates skipped

Nact = number of active bounds at final generalized Cauchy point

Projg = norm of the final projected gradient

F = final function value

* * *

N Tit Tnf Tnint Skip Nact Projg F

3 11 14 1 0 0 7.403D-08 2.308D+00

F = 2.3081388933012512

CONVERGENCE: NORM_OF_PROJECTED_GRADIENT_<=_PGTOL

Unobserved Components Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: CPIAUCNS No. Observations: 191

Model: random walk Log Likelihood -440.855

+ AR(1) AIC 887.709

Date: Wed, 02 Nov 2022 BIC 897.450

Time: 17:06:03 HQIC 891.655

Sample: 04-01-1971

- 10-01-2018

Covariance Type: opg

================================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

sigma2.level 0.2037 0.156 1.310 0.190 -0.101 0.508

sigma2.ar 5.2920 0.338 15.665 0.000 4.630 5.954

ar.L1 0.4005 0.096 4.161 0.000 0.212 0.589

===================================================================================

Ljung-Box (L1) (Q): 1.46 Jarque-Bera (JB): 521.69

Prob(Q): 0.23 Prob(JB): 0.00

Heteroskedasticity (H): 1.59 Skew: -1.30

Prob(H) (two-sided): 0.07 Kurtosis: 10.69

===================================================================================

Warnings:

[1] Covariance matrix calculated using the outer product of gradients (complex-step).

This problem is unconstrained.

As noted earlier, the Theano wrappers (Loglike and Score) that we created above are generic, so we can re-use essentially the same code to explore the model with Bayesian methods.

[13]:

# Set sampling params

ndraws = 3000 # number of draws from the distribution

nburn = 600 # number of "burn-in points" (which will be discarded)

[14]:

# Here we follow the same procedure as above, but now we instantiate the

# Theano wrapper `Loglike` with the UC model instance instead of the

# SARIMAX model instance

loglike_uc = Loglike(mod_uc)

with pm.Model():

# Priors

sigma2level = pm.InverseGamma("sigma2.level", 1, 1)

sigma2ar = pm.InverseGamma("sigma2.ar", 1, 1)

arL1 = pm.Uniform("ar.L1", -0.99, 0.99)

# convert variables to tensor vectors

theta_uc = tt.as_tensor_variable([sigma2level, sigma2ar, arL1])

# use a DensityDist (use a lamdba function to "call" the Op)

pm.DensityDist("likelihood", loglike_uc, observed=theta_uc)

# Draw samples

trace_uc = pm.sample(

ndraws,

tune=nburn,

return_inferencedata=True,

cores=1,

compute_convergence_checks=False,

)

Auto-assigning NUTS sampler...

Initializing NUTS using jitter+adapt_diag...

Sequential sampling (2 chains in 1 job)

NUTS: [ar.L1, sigma2.ar, sigma2.level]

Sampling 2 chains for 600 tune and 3_000 draw iterations (1_200 + 6_000 draws total) took 64 seconds.

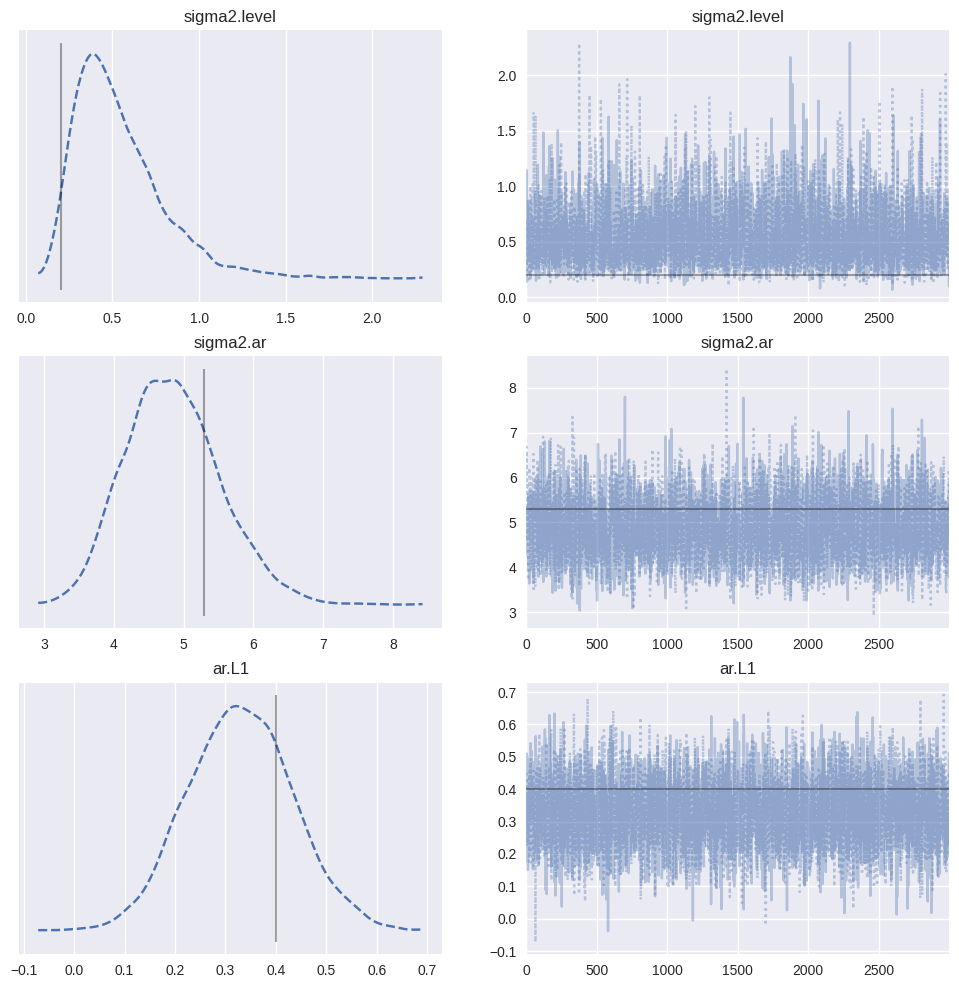

And as before we can plot the marginal posteriors. In contrast to the SARIMAX example, here the posterior modes are somewhat different from the MLE estimates.

[15]:

plt.tight_layout()

# Note: the syntax here for the lines argument is required for

# PyMC3 versions >= 3.7

# For version <= 3.6 you can use lines=dict(res_mle.params) instead

_ = pm.plot_trace(

trace_uc,

lines=[(k, {}, [v]) for k, v in dict(res_uc_mle.params).items()],

combined=True,

figsize=(12, 12),

)

<Figure size 800x550 with 0 Axes>

[16]:

pm.summary(trace_uc)

[16]:

| mean | sd | hdi_3% | hdi_97% | mcse_mean | mcse_sd | ess_bulk | ess_tail | r_hat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sigma2.level | 0.539 | 0.264 | 0.155 | 1.018 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 3876.0 | 3835.0 | 1.0 |

| sigma2.ar | 4.852 | 0.679 | 3.608 | 6.105 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 3334.0 | 3820.0 | 1.0 |

| ar.L1 | 0.329 | 0.103 | 0.143 | 0.528 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 4058.0 | 4111.0 | 1.0 |

[17]:

# Retrieve the posterior means

params = pm.summary(trace_uc)["mean"].values

# Construct results using these posterior means as parameter values

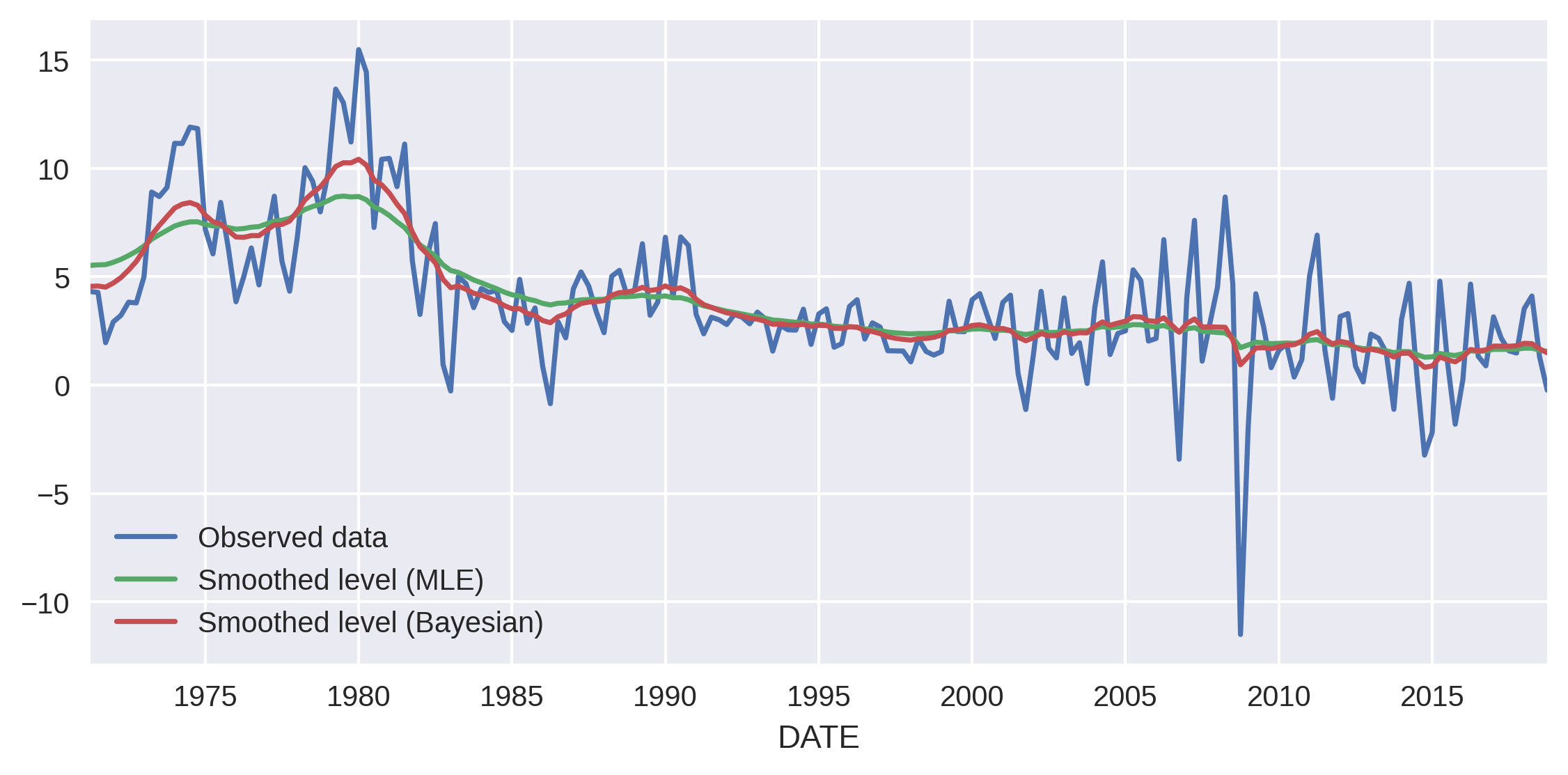

res_uc_bayes = mod_uc.smooth(params)

One benefit of this model is that it gives us an estimate of the underling “level” of inflation, using the smoothed estimate of states.smoothed attribute. In this case, because the Bayesian posterior mean of the level’s variance is larger than the MLE estimate, its estimated level is a little more volatile.

[18]:

# Graph

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9, 4), dpi=300)

# Plot data points

inf["CPIAUCNS"].plot(ax=ax, style="-", label="Observed data")

# Plot estimate of the level term

res_uc_mle.states.smoothed["level"].plot(ax=ax, label="Smoothed level (MLE)")

res_uc_bayes.states.smoothed["level"].plot(ax=ax, label="Smoothed level (Bayesian)")

ax.legend(loc="lower left");